Welcome to Holden Court, a New Effort at Media Criticism

For The Inaugural Article, Let’s Revisit Covid Coverage

Why we’re here: I’d like to better chronicle the things the media get wrong, and better understand why the press err in the way that they do.

Media criticism (on the right particularly) is often unmoored from the specifics of what the media actually said and did. Not only does that make it less convincing to the majority of Americans who still trust the information they get from national news outlets, but it also makes it more difficult to build a longitudinal case that the way the media records history as it happens is a problem.

I’m going to try to connect the dots, maintaining the history of major press failures and explaining why they matter. For many of you, these examples won’t be new. But hopefully some of the primary source material is — and that’s the value add I’m trying to provide, more archeologist or historian than talking head or pundit. The bones matter, both for understanding what the mainstream media said, and what it means for the way we think about recent history.

A particularly salient example that I wanted to offer by way of introduction is the early media coverage of Covid-19 in 2020.

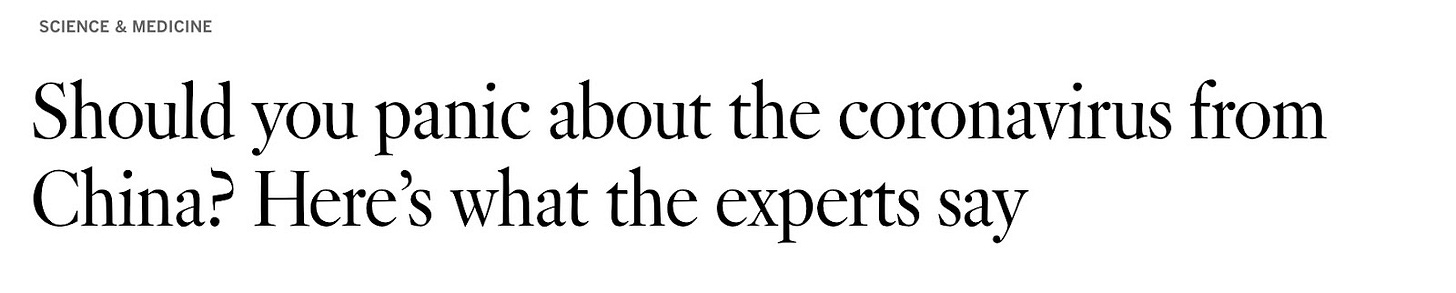

The coverage: I think we’re already forgetting some of the contours of what the media said about Covid-19, starting four years ago when the first cases started spreading out of China and to the United States. The initial coverage declared that the new coronavirus was nothing to panic about. A Business Insider piece in late January 2020 ran under the headline: “The flu is a far bigger threat to most people in the US than the Wuhan coronavirus. Here's why.”

The Los Angeles Times said that, while a scary story about a new virus might play well in Hollywood, it didn’t describe the risk then facing Americans from Covid. “‘Don’t panic unless you’re paid to panic,’” they quoted an expert as saying.

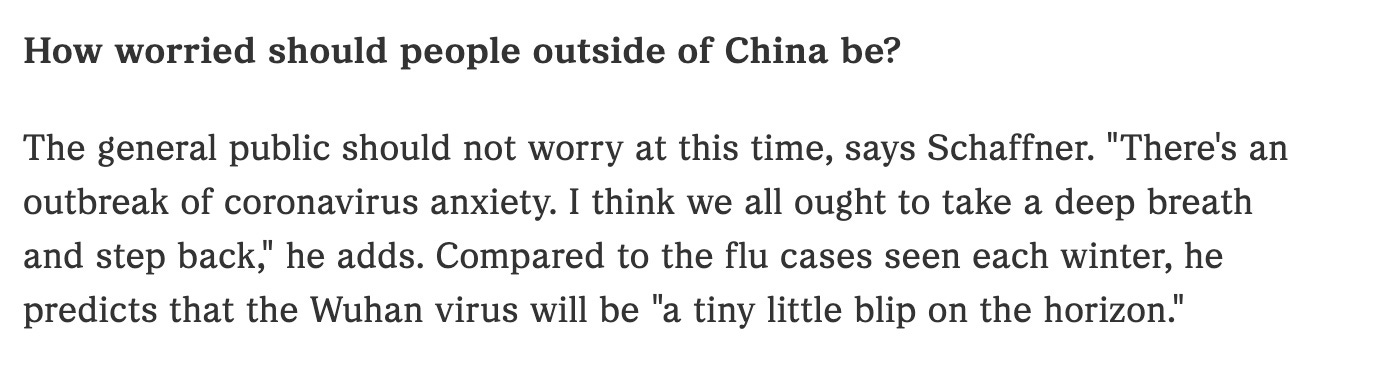

NPR cited an expert to say that the real issue was “Covid anxiety,” an “outbreak” of which was leading people to make rash decisions, in a straight news piece arguing that the flu was a much greater threat than this new disease out of China.

A USA Today piece initially published in Kaiser Health News claimed that the flu “poses a far greater threat to Americans than the coronavirus from China that has made headlines around the world.”

That sentiment was common in January and February 2020 across outlets, including Washington Post, NPR and New York Times.

The media tone at the time was typified by the headline and subhead of a Slate piece from January 24:

Things were different back then.

As death counts soared and we learned more about the disease, the coverage shifted, and the same claims the media had made in January and February were unsayable by March. When former President Donald Trump compared the risk of Covid to the flu – a media mantra mere months before – the press response was outrage. Angry fact checks from NPR, Washington Post, Reuters, CNN and others pushed back, claiming the president was endangering Americans for suggesting the same thing their self-selected experts had just gotten finished doing.

But outlets really adopted the harsher tone we all remember when lockdowns – government requirements that businesses close and people avoid going outside – started to lift in certain states in late Spring 2020.

Now there were the makings of a traditional skirmish as documented by the mainstream media: two sides with opposing views, a political party on either side of the equation and well-articulated (if hotly contested) stakes involved. On the right, governors, the president and other voices wanted to see states return to normal, or as close as normal as was possible in the throes of Covid, with social distancing, masks and other safety measures. For the left, this “Neanderthal thinking” was tantamount to murder.

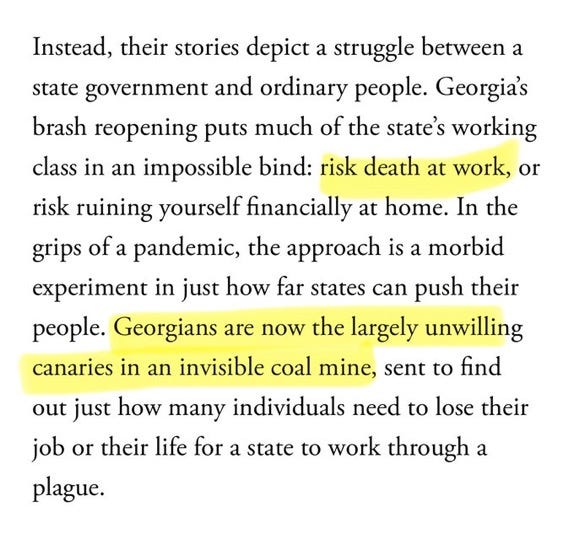

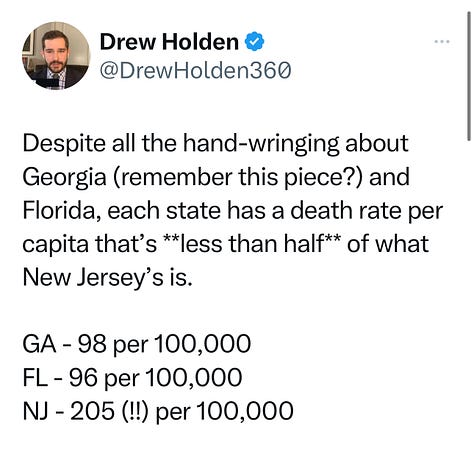

The media line was more or less the same. The Atlantic called Georgia’s reopening an “experiment in human sacrifice” in the headline of a piece that went on to claim that ending lockdowns, “puts much of the state’s working class in an impossible bind: risk death at work, or risk ruining yourself financially at home.” It went on to claim that, ”the approach is a morbid experiment in just how far states can push their people. Georgians are now the largely unwilling canaries in an invisible coal mine, sent to find out just how many individuals need to lose their job or their life for a state to work through a plague.”

The Atlantic wasn’t alone. The Washington Post called reopenings a “deadly error.” For USA Today it was a game of “Russian roulette.”

Still others took issue with the animating spirit of those who wanted to reopen. CNN said the desire to allow businesses to reopen with health measures in place was a “downright dangerous” application of utilitarianism.

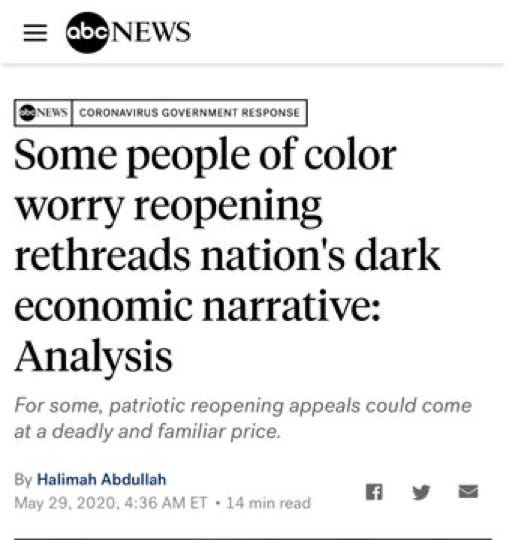

And the effort, to hear the media tell it, was racist, willing to sacrifice black and brown bodies for the sake of an economic moloch that served white people’s interests. So said Vox, Associated Press and ABC News.

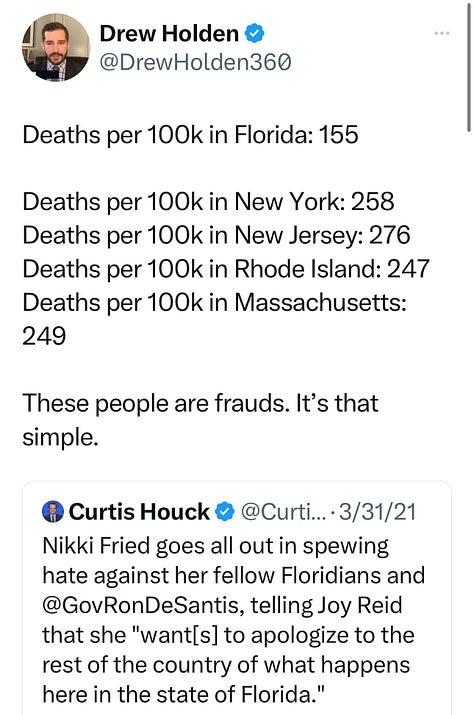

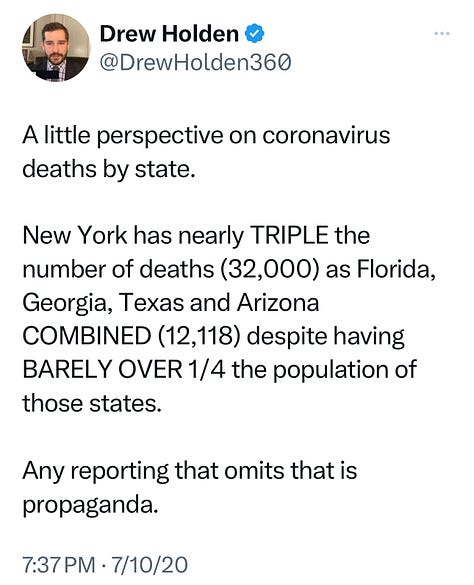

These predictions didn’t come to pass. While many Republican-governed states eventually saw their death tolls rise beyond blue states, owing to poor vaccine adoption and broader health problems endemic to many states in the American South and West, the short-term spike never came, as I liberally pointed out on Twitter.

What outlets seemed to believe needed to happen then were harsh lockdowns. The virus that the media had recently likened to the flu could now only be brought to heel with “harsh steps” (New York Times) like cajoling everyone to stay home indefinitely or even “a national quarantine” (Politico) that dispensed with individual autonomy altogether. Thankfully these national requirements didn’t come to pass.

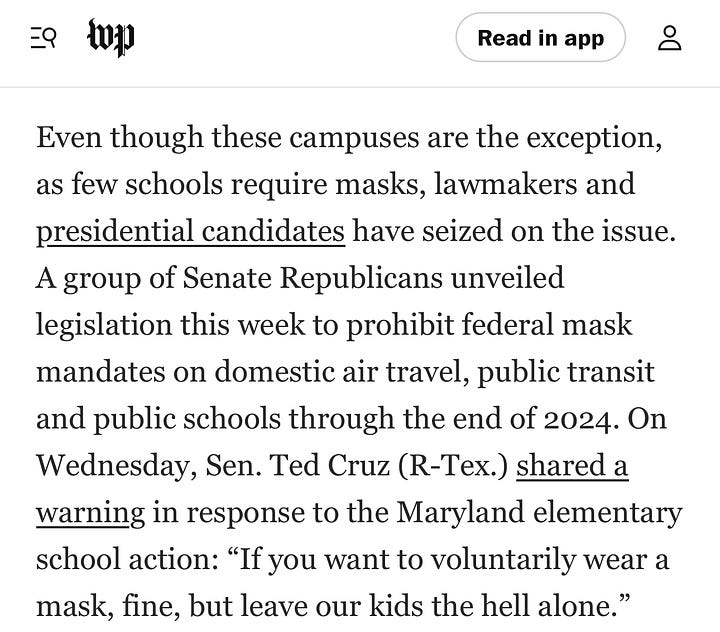

But one area where harsh closures did happen were public schools. Even though we knew at the time that children recovered faster from Covid and faced reduced risks of death or serious consequences compared to adults, many on the left and in the media pushed to keep schools closed. The details will be a subject of another piece, but here’s a flavor of the headlines at the time, in 2020 and early 2021:

The facts: Hindsight is easy on something like a global pandemic. Hard decisions had to be made in the moment with a limited amount of evidence about a new disease that was killing people and spreading quickly. Of course there would be mistakes made in the fog of war.

But we didn’t know nothing, particularly about how damaging it was to keep people under lock and key, away from friends, family and the things they cared about. We knew at the time that lockdowns had serious consequences for mental and physical health. Smarter people than I have explained the damage isolation does to people young and old, from increasing heart disease and diabetes to undermining mental health and increasing the risk of suicide. That knowledge got short shrift in media coverage back then.

I wrote about it in late 2020 for the New York Times, pointing out that the cost of lockdowns was so high as to be prohibitive unless things got much, much worse.

I should’ve given more space to the impacts on children, who were often treated as the sacrificial victims in lockdown decisions, despite facing a miniscule risk from the virus. Instead, we were told that children would suck it up. The head of the American Federation of Teachers, Randi Weingarten, famously said that kids would be “resilient” when it came to learning loss.

The data make clear that it was never a reasonable expectation to have.

Everyone got things wrong, including your author. I supported mandatory vaccines on Twitter and deferred to the experts on Facebook at the start of the pandemic. Those were obviously bad calls for someone with a small but not negligible platform online.

The impact of the media, en masse, getting these things wrong is many orders of magnitude larger. Governments across the country relied on media doomcasting in adopting harsh lockdown measures. But the press went right back to making more recommendations – always seeming to support more invasive measures or attacking conservatives for opposing such measures’ readoption.

The other problem – something I’m hoping to explore through this researching and writing endeavor – is the lack of accountability for the press in the errors they made. In writing this piece, I revisited all of the original links to these pieces, which still appear mostly in their original forms (and without editor’s notes or other corrections). The clear contradictions with prior coverage and inaccuracies go unremarked.

The so-what: One question I’m trying to better understand through this research and writing is: Why does the media get these types of stories wrong, repeatedly, and always in the same direction? Did outlets knowingly inflate the dangers of Covid to capitalize on the panic-porn-styled coverage at a time when readers were already scared and budgets were under pressure? Were journalists, a disproportionately anxious crowd, just more alarmed about a novel virus than they had reason to be? Were they blinkered about the consequences of lockdowns because so many journalists come from well-to-do families and communities, who could (and did) adjust more easily? Is it all just liberal media bias run amuck?

I don’t know yet. But I’m looking forward to discussing it with you.

The question of what motivates media missteps goes beyond Covid. Did the press buy “Russian Collusion” just because they hate Trump? Was the former president always just a ratings target, no matter how much covering him the way the press did undermined their credibility? Getting a better understanding of these motivating factors can help improve the first rough draft of history, or at least understand why that initial draft may need substantive revisions.

I don’t know if I’ll ever come to a definitive conclusion about what I think is the key factor. But like the current state of media criticism more broadly, I don’t think we — those who write and talk and tweet about the media — have approached this question in a grounded, textual way, relying on what outlets and journalists really said. But I think doing so is important, and I’ve got the receipts.

So, why pay?: I’ve been doing the threads as yeoman’s work for a long time, and I’ve learned a lot from doing so. But as I get older, and in the wake of some health concerns (more on that at the About page), I’ve got to be realistic about where I spend my time and energy, and what the return looks like for the effort. The threads are a ton of work, and sometimes get really good engagement (3.5 million views on X on the last one) but the payoff is just the feeling that I’ve done something good and some internet validation. I want to keep bringing them to all of you, without a paywall, while doing more work to make them better and more impactful. That includes investing time to build out a more robust analysis of how the media got it wrong. Your funding will make that possible.

Plus, a number of you have asked in years past how you can support my work. I think Substack will make that possible in the most direct way.

Whether you’re able to support me financially or not, I’m happy you’re here.

Signed up on the strength of your excellent laptop piece. Then I read a couple others, including your brain cancer story, and I’m ready to pony up. You’re a brilliant writer, and I say that as someone who spent 30 years in journalism including 25 as an editor on a giant metro daily. I know a brilliant writer when I see one. (They’re rare.) Keep going and savor the small things.

Just subscribed.